This is a blog version of the first chapter of the yet to be published dissertation of Robert van Doesburg that is also available as a publication. See https://regels.overheid.nl/publicaties/building-a-framework-for-norms-and-rules

After discussing a frame-base for the interpretation of norms and rules, see (Van Doesburg 2025e), in this paper we will present a framework for working with norms and rules in the context of tasks.

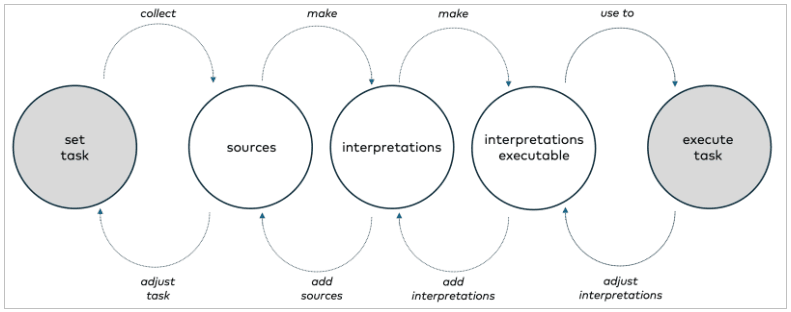

This framework defines the operational boundaries within which norms and rules are used. It is structured around the setting of a task and the subsequent execution of that task, inherently adopting an action-based perspective.

The first step of making a framework for norms and rules, is defining what the framework is for. What is the task to be accomplished, the problem that needs solving or the question we want answered? This step sets the boundaries of our analysis, and the point of reference to determine whether the task is executed successfully or not.

The normative component of the framework is constituted by three steps:

- ‘collecting sources’ that contain the necessary normative content,

- the extraction of norms and rules from these sources through a process of ‘literal interpretation’,

- subsequently, refining the model by assessing whether additional knowledge is required to ‘make interpretations executable’.

The three-step normative framework can be elaborated to a five-step task model:

- ‘set task’,

- ‘collect sources’,

- ‘interpret sources’,

- ‘make interpretations executable’, and

- ‘execute tasks’.

Figure 7.1 is a graphical representation of this model.

Figure 7.1 is a graphical representation of this model.

In this paper, we focus on three primary tasks: ‘task definition’, ‘source collection’, and the ‘interpretation of regulatory sources. The development of executable interpretations lies beyond the scope of this work and is designated for future research.

In previous studies (Van Doesburg and Van Engers 2018; Van Doesburg 2019; Van Doesburg and Van Engers 2019), we applied norms and rules derived from the interpretation of regulatory sources to individual cases.

However, we have not yet succeeded in formulating a general model for executable interpretations. Moreover, we have not established a clear distinction between the general characteristics of executable rules (e.g. the temporal and spatial conditions under which a fact is qualified, or an action is deemed valid) and the context-specific characteristics that differentiate executable rules used by, e.g., humans from those that can be automatically executed by machines.

It is important to note that ‘task execution‘ can be discussed independently of having ‘executable norms and rules’. In the case studies (Van Doesburg 2025g; 2025h) presented in, we will examine how our interpretations contribute to the task set for the case. However, a comprehensive discussion of the relationship between ‘executable interpretations’ and ‘task execution’ requires further insight into the nature of ‘executable interpretations’.

In the conclusion of this paper, we will discuss the incremental aspects of building frameworks of norms and rules. Specifically, we will address how normative text interpretations can be refined step by step, how cooperation can be facilitated, and how disagreements and disputes can be resolved.

1 Setting the task

A task can either relate to physical reality (‘dig a hole’ or ‘build a house’) or to institutional reality (play football, start a company, pay for dinner or vote for parliament). In this paper, we are interested in institutional tasks, which can only exist in a normative framework.

The completion of an institutional (or normative) task depends on qualification. The task consists of a set of normative ‘actions’, and the question is whether the ‘actions’ are executed validly, and under circumstances where the ‘precondition’ was true.

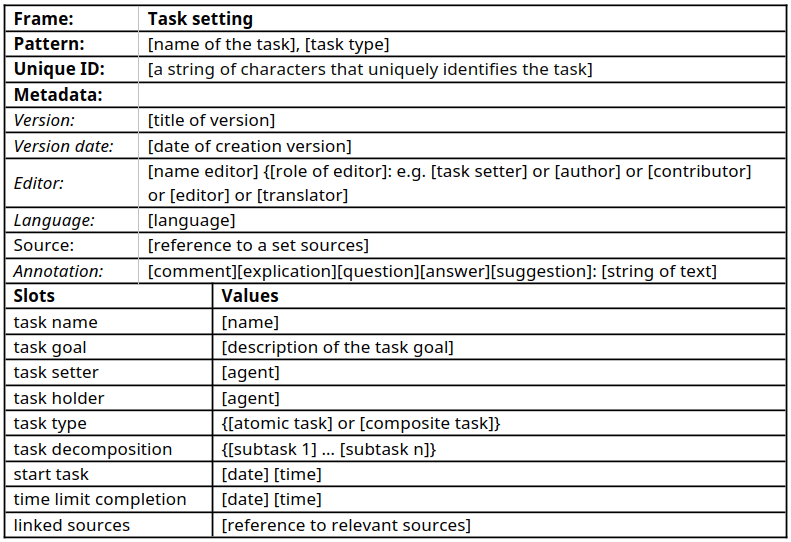

Our frame for tasks is built on the work of Pepijn Visser (1995) and the role of tasks in the CommonKADS method (Schreiber et al. 1994, 12-15; cf Wielinga et al. 1992).

A frame for task setting

A task must have a goal, and it can be either primitive (we will use the word ‘atomic’)1 or composite. Visser (1995, 41-42) also includes ‘input roles’ and ‘output roles’, but we choose to leave those out of the task setting frame since we consider those part of the interpretation frames, see (Van Doesburg 2025e) and section 3.3 of this paper.

What Visser (1995, 41) calls ‘task control structure assumption’ we include in a slot for the start of a task (‘start task’) and a time limit for its completion (‘time limit completion’). Other activities that can be seen as elements of a task control structure can be added as separate task frame.

The context of a task includes two agent roles: a ‘task setter’ (for the agent holding the task to set a new task and the authority to assign it) and a ‘task holder’ (the agent responsible for executing the task).

Based on Breaux’ (2009, 29, 31) frame for legal requirements acquisition we made a frame for tasks, see table 7.1. There might be other solutions for modeling tasks, but since this solution fits our purpose, and since we consider task models on setting and executing tasks merely as the boundaries of the scope of this paper, we will not be looking for alternatives.

The decomposition of composite tasks can be expressed by free format descriptions of activities, or by using proper normative ‘acts’, made by interpreting sources.

Table 7.1: A frame for task setting.

Table 7.1: A frame for task setting.

To support the incremental nature of making frameworks of norms and rules, we also added a unique identifier and metadata to allow for versions and cooperation. For practical reasons we also added the possibility of making language versions.

Since the goal of the task setting is to set the boundaries of a framework for norms and rules, we link the task to a set of sources. In the next subsection we will introduce a frame for sources.

Tasks can be about virtually anything

Tasks can be big or small. They can concern a single case or multiple cases. Tasks can be about the interpretation of sources, or about deciding a case, reviewing a single decision or auditing the process of deciding on a set of cases.

It is a task to make instructions for agents that decide cases, or to make specifications for decision support systems. Tasks can be about the extraction of all acts that can be found in a law act (Van Doesburg 2025h), or about the assessment of behavior in the past (Van Doesburg and Van Engers 2018b). Comparing lawsuits in countries with different legal systems (Van Doesburg and Van Engers 2018a) can also be seen as a task.

Tasks may concern the application of existing norms to cases, or about making new norms by interpretation of existing sources. Making new sources, e.g. drafting new laws and regulations, making amendments for existing ones, in order to implement policy changes, can also be represented as a task.

Our framework for norms and rules is not aimed to do any of these tasks in particular. It is designed for all tasks, and for all agents affected by the norms and rules concerned. As long as these tasks are about ‘actions’ regulated by norms and rules.

Whatever the task, after it is set, the next step is always to collect the sources that contain regulatory knowledge concerning the task. If we are lucky, that knowledge is readily available, often we have to search for it.

2 Collecting sources

What do we need to be able to get the norms and rules from a set of sources? We need a reference to those sources (in order to be able to build a collection), we need the smallest containers of meaning in those sources (in order to be able to reuse interpretations if those containers occur multiple times, and because it is easier to agree on interpretation of simple text fragment then about the meaning of a complex source). Furthermore, we need the structure of the source that allows us to make complex sources such as enumerations, documents, law acts or books (so we can make context-related interpretations).

In this section we describe the structure of sources of knowledge. We will be defining what we need to know of a source in order to select the sources relevant for a task, and necessary for the interpretation of sources into a framework for norms and rules.

Sources contain symbolic representations of knowledge. In this paper, we will focus on written sources, although the frames we propose can also be used for other manifestations used for the representation of knowledge, e.g. video, audio recordings and pictures.

Written sources are text fragments ordered in documents. In this section we will presuppose that written sources are build out of three basic elements, that are foundational for our use of language, but not totally independent of each other: ‘phrases’, ‘clauses’ and ‘sentences’.

We will show that we can build all kinds of document structures using these types of text fragments. If one wishes, ‘phrases’, ‘clauses’ and ‘sentences’ can be broken down into even smaller components, i.e. words and characters.2 Characters then can be decomposed into letters, digits, punctuation, and other types of symbols.

2.1 Sources of norms can be found in documents

Sources of norms, or normative texts, are sources that contain symbolic representations that can be interpreted as norms and rules.

Sources of formal norms

Formal norms require sources that codify norms in official documents.

Sources of non-formal norms

Non-formal norms do not require explicit sources in order to exist, but they do need sources in which observations and descriptions are laid down to make it possible to have a meaningful debate on the nature of a non-formal norm.

Non-formal norms can have any type of source, including unwritten habits, folkways, and customs that are not (yet) laid down in symbolic representations.

If we are using unwritten sources for the analysis of non-formal norms, observations should be written down as part of the process of collecting sources. The study of human behavior is, on this point, not different then the study of other types of animals:

One thing the early ethologists had in common was the wish to return to an inductive start, to observation and description of the enormous variety of animal behaviour repertoires and to the simple, though admittedly vague and general question: "Why do these animals behave as they do?"

(Tinbergen 1963, 411)

Proposition 7. Norms (and rules) have a source, the interpretation of the source is the norm (or the rule).3

2.2 What are ‘phrases’, ‘clauses’ and ‘sentences’?

Since it is our goal to map written sources in natural language onto slots of normative relation frames, we must first define the smallest unit of meaning in these sources. Additionally, we need to develop a taxonomy that allows us to reconstruct the original source (or sources, we are referring to.

We consider sentences to be the basic container of meaning. Sentences are:

A series of words in connected speech or writing, forming the grammatically complete expression of a single thought; in popular use often … such a portion of a composition or utterance as extends from one full stop to another.4

Music. A complete idea, usually consisting of two or four phrases.

Logic. A correctly ordered series of signs or symbols that expresses a proposition in an artificial or logical language.

(OED, s.v. “Sentence, n.,” 2024).

Sentences can be simple or complex. An independent clause can be a simple sentence, or part of a complex sentence. A dependent clause is part of complex sentence. Clauses contain a subject and a predicate (OED, s.v. “Clause, n.,” 2024).

A phrase can be just one word5, but must be smaller than a clause, since it does ”not include both a subject and a predicate or finite verb” (OED, s.v. “Phrase, n.,” 2024).

Phrases, clauses and sentences are the basic components of text documents.

Simplification of sentences

We choose to do the simplification of sentences containing disjunctions or conjunctions to be part of the interpretation of that sentence because there are many forms to make complex sentences, see e.g. Allen and Tury (2007). It is not always possible to break complex sentences down into simple sentences or clauses without doing some interpretation of the meaning of a sentence. For practical reasons we leave this task of simplification to interpreters.

Enumerations

A sentence containing an enumeration, on the other hand are more structured and can more easily divided into components, i.e.: • an introductory clause, • a list of items, and sometimes • a final clause.

These elements are ‘phrases’ or ‘clauses’, not full sentences.

Titles and headings

Another reason for introducing ‘phrases’ and ‘clauses’ is to enable the creation of ‘titles’ and ‘headings’. These are typically not full ‘sentences’ but can convey meaning. Additionally, they are essential making complex written structures like documents or books.

So, although we consider sentences the basic units of knowledge, we also propose the use of ‘text fragments’ or the type ‘phrase’ and ‘clause’.

2.3 How to build a document from ‘text fragments’?

How can we (re)create text document from a set of ‘text fragments’ of the types ‘phrases’, ‘clauses’ and ‘sentences’? And why do we want to be able to create and recreate documents from their constituents?

An example

Text documents, especially documents concerning legal text, can have many amendments. The Dutch General Administrative Law Act6 enacted in 1994, has more than 300 versions. Since every version only differs slightly from its predecessor, it makes sense to create a knowledge base consisting of the initial version, and all changes. It is much more efficient to recreate all versions from that knowledge base, rather than publishing a new version of the whole document, anytime a small change is being made to it. However, the latter is the current practice.7

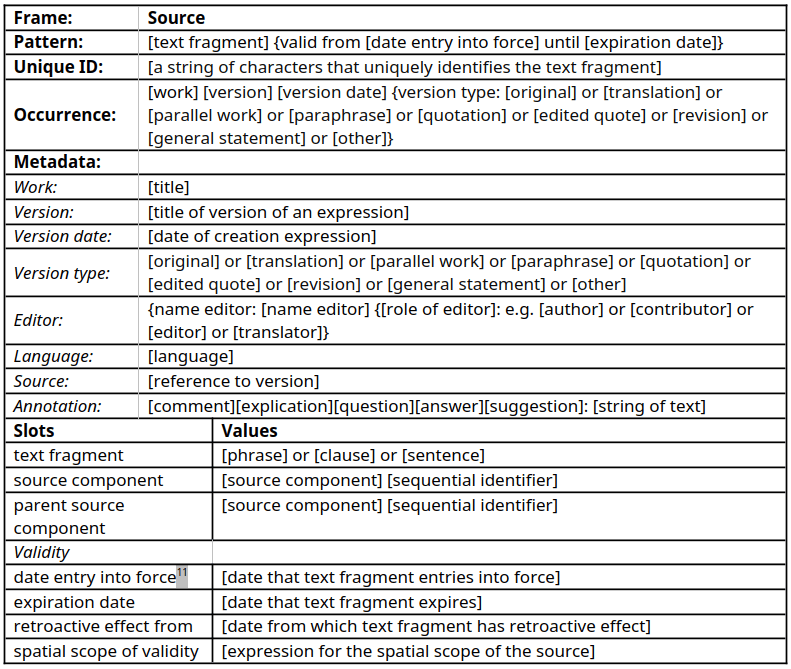

2.4 Frame based on Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR)

We propose a frame base for modeling the meta data of ‘text fragments’ in such a way that these can be used:

- as a basis for interpretation, and

- to trace every interpretation back to its source.

Our frame is based on the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (Byrum et al. 2009; IFLA 2024).

The FRBR is divides the characteristics of bibliographic records into four categories:

- ‘work’ (a distinct intellectual or artistic creation),

- ‘expression’, or as we prefer ‘version’ (the intellectual or artistic realization of a work),

- ‘manifestation’ (the physical embodiment of an expression of a work),

- ‘item’ (a single exemplar of a manifestation).

These categories of intellectual or artistic creation, can be related to persons (individual persons or institutions8) and to other characteristics9 of these creations.

For making normative analyses to build a framework for norms and rules, we will only need the first two categories: ‘works’ and ‘expressions’ (or ‘versions’). This allows us to build a knowledge base of ‘text fragments’ that can be used for interpretation and can be traced back to ‘works’ and ‘version of works’.

Linking those ‘text fragments’ to ‘manifestations’ and ‘items’ can be done, if necessary, using the existing FRBR-standard.

Metadata of the source frame

The distinction between metadata and slots is rather arbitrary for the source frame, that is for every slot except the ‘text fragment’ itself. We chose to keep the metadata consistent with the set of metadata we used in the other frames (adding only ‘works’ since that is related to ‘versions’).

Slots of the source frame

The frame, see table 7.2, connects a text fragment to their occurrences. For every occurrence we have a set of metadata, and some slots. We have slots for ‘text fragment’, ‘source component’ and ‘reference’.

The ‘text fragment’ is either a ‘phrase’, a ‘clause’ or a ‘sentence’. A ‘sentence’ can be ‘simple’ or ‘complex’ or an ‘enumeration’. An ‘enumeration’ has ‘items’ and can have an ‘introductory clause’ and it can have a ‘final clause’.

There are slots for marking the type of source component of a text fragment, and the parent of that source component. Common types of source components are chapters, sections, or paragraphs. More exceptional components of bibliographical works include books, parts, divisions, articles, or epilogues. The source component can have a sequential identifier for numbering source elements. There is no restriction to the kind of components used in a source, nor to their number.

Because we not only mark the source component of the fragment, but also the parent source component (e.g. the parent source component of a sentence can be a paragraph, a section or a chapter), we are able to build a taxonomy of the components of a source. By marking the parent of every source component, the document structure is laid down in the frames.10 See table 7.3 for an example.

Slots for validity

In the source frame we also added slots for the validity of the source. We added slots for date entry into force, expiration date, retroactive effect from and spatial scope of validity.

These slots are added for practical reasons. Although the validity of a norm is clearly related to interpretation, and not to the source itself, there are practical reasons to put knowledge on the validity of a source in the source frame.

The interpretation of the meaning of a sentence, can be divided into two categories:

- the normative meaning of the sentence, and

- information on when and where that sentence is valid.

Table 7.2: A frame for sources11

Table 7.2: A frame for sources11

Since, in some cases knowledge on the date entry into force, expiration date, retroactive effect from is part of the source, e.g. regulations of the European Union (EU 2015, 68-73) and the Dutch national government (Ministerie van Justitie en Veiligheid 2024), we chose to make slots for this information in the source frame. We added information on the spatial scope of validity since time and space are related concepts (Kelsen 1967, 12-14; Lorini and Loddo 2017; Einstein 1905).

As a result, knowledge concerning the validity of a sentence, clause or phrase in time and space can be registered in source frame. Adding this knowledge to frames for interpretation is much more complicated since one ‘text fragment’ can be part of multiple interpretation frames, see (Van Doesburg 2025e) and section 3.3.

Furthermore, the validity of the formal norm is related to the source, the official document that contains the codified norm, not to its interpretation. This is best illustrated by the nulla poena sin lege principle in penal code: no punishment without law. It is the date of entry into force of a penal regulation that sets the date from which a punishment can be imposed, not the date on which an interpretation has been made.

Therefore, we will store knowledge on validity in time and space in sources frames rather than in interpretation frames, nevertheless, the assignment of validity to a text should be considered an act of interpretation.

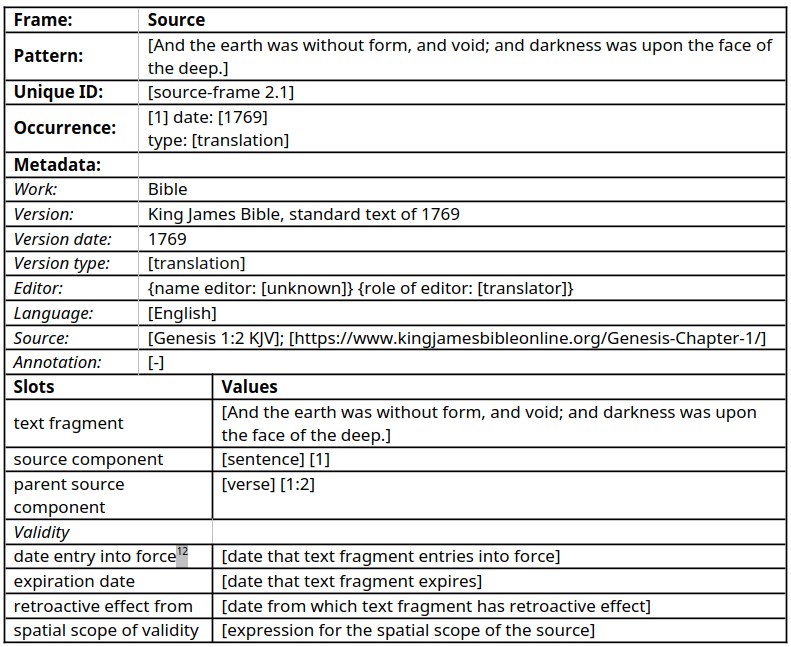

2.5 An example: Verse 1:2 KJV in a source frame

To give an example of the working of the source frame, we will give an example using the sentence “And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep.” It is the second sentence of the first chapter of the book of Genesis of the old testament in the King James Bible in the version of 1769.

Table 7.3: Genesis 1:2 KJV in a source frame.12

Table 7.3: Genesis 1:2 KJV in a source frame.12

As a reference we added the common reference format for references to the Bible (‘Genesis 1:2 KJV’) and a link to the kingjamesbibleonline.org. Any other reference format can be added. The frame has no restrictions on the number of references nor for the type of reference used.

Kingjamesbibleonline also contains, e.g., the first version of the King James Bible from 1611, in which verse 1:2 was a single sentence and written in Early Modern English (“And the earth was without forme, and voyd, and darkenesse was vpon the face of the deepe: and the Spirit of God mooued vpon the face of the waters.”) and the original Hebrew text.

We could make additional frames for these versions and link them together. We could also link to the occurrence of the text in other ‘works’. The book of Genesis is not only a part of the Bible, but also of another religious work: the Torah.

Text fragments from the Bible are often cited, e.g. by the crew of Apollo 8 in the ‘Apollo 8 Christmas Eve Broadcast’ on 24 December 1968. This would count as an additional work. The FRBR-standard allows for the representation of the form of the version and the carrier of the manifestation of the work, so we don’t have to bother about that. Beside the video of the program there is also a transcription of NASA that contains all communication between Apollo 8 and Flight Control, which can be considered as yet another work in which the sentence occurs.

The slots for the validity of the text fragment are irrelevant for this type of source and therefore remains empty.

3 Interpreting sources

After the sources are collected, we can start to interpret them. In this paper, we see norms and rules as concepts for regulating behavior of one human as against another. Therefore, we see norms and rules as essentially relational. Without there being at least two agents interacting, there is no need for norms and rules.

The normative relations theory states that there are two fundamental normative relations: ‘acts’ and ‘claims’. Both can be constituted by a combination of ‘facts’ that have one of nine roles: ‘action’, ‘object’, ‘actor’, ‘recipient, ‘condition’, ‘operator’, ‘duty’, ‘claimant’ or ‘duty holder’. For more on this, see (Van Doesburg 2025e).

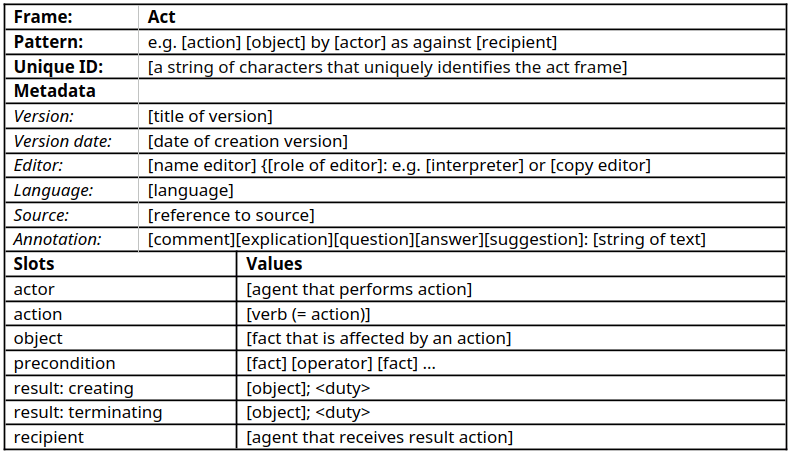

As a result, we can represent norms and rules using three types of frames: ‘act frames’, ‘claim frames’ and ‘fact frames’.13

3.1 A frame for acts

The ‘act’ consists of ‘action’ by an ‘actor’ directed at an ‘object’. The ‘action’ is valid if the ‘precondition’ is true. A valid ‘action’ has a ‘result’ that either creates or terminates an ‘object’ or a ‘duty’. The ‘result’ of the ‘action’ is intended for another agent: the ‘recipient’.

Table 7.4 is an extended version of the frame presented in (Van Doesburg 2025e), it contains the metadata we introduced for the task frame and the source frames.

Table 7.4: The expanded ‘act frame’.

Table 7.4: The expanded ‘act frame’.

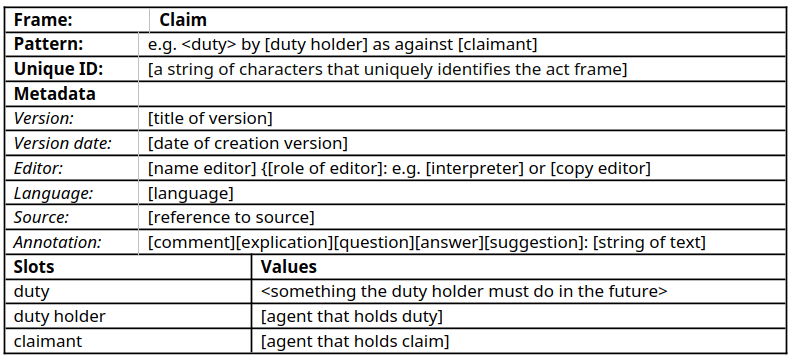

3.2 A frame for claims

The second fundamental normative relation is the ‘claim’, which is the relation between a ‘claimant’ and ‘duty holder’ concerning a ‘duty’. The ‘duty’ is a reference to an ‘act’ that a ‘duty holder’ must do at the request of the ‘claimant’. Table 7.5 is an extended version of the frame presented in (Van Doesburg 2025e), with the extra metadata we introduced in this section.

Table 7.5: The expanded ‘claim frame’.

Table 7.5: The expanded ‘claim frame’.

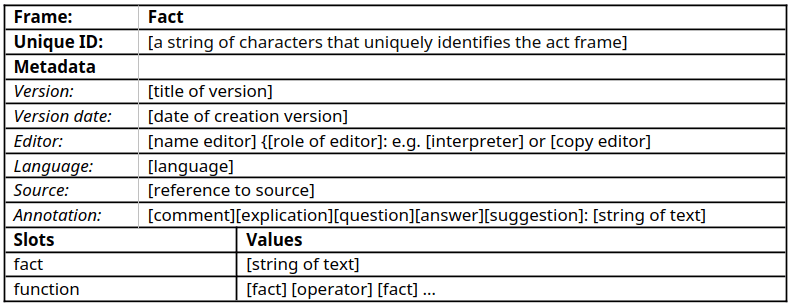

3.3 A frame for facts

The ‘fact frame’ is a frame that can be used to elaborate the constituents of the ‘act frame’ and the ‘claim frame’. Table 7.6 is an extended version of the frame presented in (Van Doesburg 2025e).

Table 7.6: The expanded ‘fact frame’.

Table 7.6: The expanded ‘fact frame’.

Alternative interpretation schemes for norms and rules

It is not our goal to make a framework for norms and rules that can be used with only one method for interpreting normative text. One can choose to build and method for the interpretation of normative texts.

By creating a protocol that proposes a generic structure for formulating ‘tasks’ and allows for decomposing ‘sources’ into individual sentences (and smaller components if necessary), we have put in place an infrastructure that not only supports making interpretations using normative relation theory, but also allows for interpretations using any other schemes for normative interpretation. This also allows for making detailed comparisons between the interpretation of the same set of sentences, using multiple interpretation schemes. To make detailed comparison between multiple interpretation schemes easier, we advocate maximum traceability to literal phrases in sources.

We argue there are only two fundamental normative relations, and that these relations can be represented by a set of facts. If this hypothesis is correct, this would mean that we should be able to represent the results of any other normative interpretation scheme using only ‘act frames’, ‘claim frames’ and ‘fact frames’. Finding a situation where we need additional concepts to interpret a source of norms, our hypothesis is falsified. We have, as yet not found an example that falsifies our hypothesis.

4 Incremental improvement of a framework for norms and rules

Building a framework for norms and rules is an incremental process. Usually, we start by setting a preliminary version of the task. We collect some sources, and we start by finding sentences that contain the basic elements of an act, i.e. actions, agents, and objects that are affected by actions.

The knowledge we gain by collecting sources, or by interpreting them, might lead to new insights that brings us to change the task description, add additional sources, or we change interpretations. These will be represented in new versions of the task definition, the set of sources, or the interpretation.

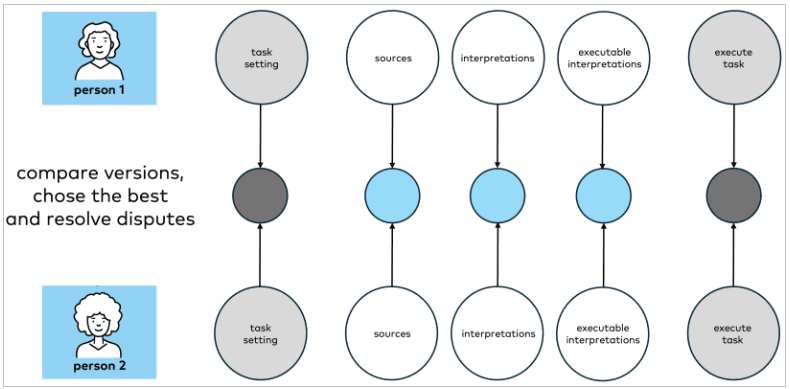

At some point, we might want to compare multiple versions of the system and decide which one we like most. This requires us to be able to compare multiple versions of the system, see figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2: Versions of a framework for norms and rules.

Figure 7.2: Versions of a framework for norms and rules.

Reading collected sources can be a reason for changing the description of the task, e.g. because these sources might use other terms than used in the task description. Interpretation of sources might lead to searching for additional sources because parts of the interpretation remain empty, or because interpretations spark new questions. Planning for the executing of norms and rules in a specific context can spark a search for additional norms and rules, or of clarifications of some kind, because the humans that will be working on the task need it, or the machines that will be used to execute parts of the task require additional specifications.

The steps of the protocol provides structure for the comparison of multiple versions of a model of norms and rules. The separation of concerns (task definition separated from source collection, source collection separated from literal interpretation, literal interpretation separated from executable interpretation, executable interpretation separated from task execution) adds precise description of the differences between models, and simplifies the task or choosing the best version.

Disagreements and disputes

Working in collaborative teams or as against an adversary team, is a special kind of versioning. Comparing versions with others needs not be very different than comparing two versions of the same analyst, but when disagreements are not easily solved, and evolve into more serious disputes, formal procedures might be needed.

The model for comparing multiple versions of systems of norms and rules will still be useful, see figure 7.3.

Figure 7.3: Comparing the systems of norms and rules of multiple persons.

Figure 7.3: Comparing the systems of norms and rules of multiple persons.

Whether one is comparing results in a collaborative team or between advisories (in some kind of procedure for mediation or arbitration), the first step is clarifying the differences between multiple versions of the system.

The second step is to come to a shared solution. This is done by the agents involved when versions are discussed in collaborative team, or when a dispute is solved by mediation, it is done by an arbiter in case arbitration (or when a collaborative team requires an authority to come to a decision).

The separation of the system in five separate categories, and the frameworks for representing knowledge in these categories, makes it easier to identify differences between versions, and to come to a shared interpretation. However, this is not a guarantee for success since people are extremely good in having disagreements and disputes.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we presented a framework for acquiring knowledge on norms and rules for the execution of tasks.

The framework consists of five steps:

- ‘task setting’,

- ‘collecting sources’,

- ‘interpretating sources’,

- ‘making interpretations executable’, and

- ‘executing tasks’.

In this paper we focus on the first three steps: the ‘task definition’, ‘source collection’, and the ‘interpretation of regulatory sources’. Leaving the discussion on making ‘executable interpretations’ and ‘task execution’ for future work.

‘Task execution’ can be discussed separately from making ‘executable interpretations’. There is a lot to be said on ‘literal interpretations of normative text’ in relation to the execution of ‘tasks’. However, to be able to discuss the relation between ‘executable interpretations’ and the executing of a ‘task’, we need more insight in the nature of ‘executable interpretations’.

The challenge of transforming ‘literal interpretations’ into ‘executable’ ones lies in their inherent context dependency.

‘Literal interpretations’ involves mapping phrases from normative texts onto predefined ‘interpretation frames’. However, execution occurs within a specific context, influenced by place, time, and the agent involved. If the agent is human (whether an expert or layperson) they can interpret ‘implicit information’. If the agent is a machine, its ability to recognize patterns is constrained by its design and computational capabilities. Humans understand; machines recognize patterns.

Elaboration of a framework for norms and rules

Section 1 presents a task representation model based on the work of Pepijn Visser (1995, 41-42).

Section 2 proposes a method for representing regulatory sources as structured sentences, building upon the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR).

Section 3 outlines a frame-base for the interpretation of regulatory, see (Van Doesburg 2025e) for a more detailed presentation of the frame-base.

The frame-base for interpreting regulatory sources consists of three types of frames for representing norms and rules:

- ‘act frames’,

- ‘claim frames’, and

- ‘fact frames’.

Section 4 presents a model for incremental improvement of task models, allowing comparisons across multiple versions of the model and its components. Comparisons can be made of multiple versions authored by a single person, of multiple versions made by different individuals, or for comparing version in the process of dispute resolution.

By establishing a systematic approach for acquiring and interpreting norms and rules, this paper lays the foundation for future work on executable interpretations and task execution, aiming to bridge the gap between making literal interpretations of normative texts and the practical execution of norms and rules in dynamic, context-dependent environments.

Bibliography

Aldewereld, Huib, Sergio Álvarez-Napagao, Frank Dignum, and Javier Vázquez-Salceda. 2010. “Making Norms Concrete.” In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems: Volume 1 - Volume 1, 807–14. AAMAS ’10. Richland, SC: International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems.

Alexander, Larry, and Michael Moore. 2021. “Deontological Ethics.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2021. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/ethics-deontological/.

Allen, Layman E, and Charles S Saxon. 1993. “A-Hohfeld: A Language for Robust Structural Representation of Knowledge in the Legal Domain to Build Interpretation-Assistance Expert Systems.” In Deontic Logic in Computer Science: Normative System Specification. Chichester, N.Y., USA: J. Wiley.

Allen, Layman E., and Adam W. Tury. 2007. “NewMINT Interpretation Assistance System: United States Constitution First Amendment’s Initial 1344 Interpretations.” In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law, 161–65. ICAIL ’07. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1276318.1276348.

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

Referring to ‘atomic facts’ as translation for ‘Sachverhalt’ in the English translation of Frank Ramsey and Charles Ogden of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus (Wittgenstein 2021 [1921], 2.01) ↩

-

Decomposing sentences in smaller components requires a proper definition of the concept ‘word’ that includes answers to the following questions: • Can a ‘word’ contain any symbol (or must the consist of letters)? • Must a ‘word’ have a pronunciation? • Must a ‘word’ have a lexical category (e.g. verb or noun)? • Must a ‘word’ have a semantic meaning? • How do ‘words’ compare to ‘tokens’? ↩

-

See also Shecaira (2015, 17-18). ↩

-

This definition is not very precise since it excludes every first sentence. Usually, but not always, sentences start with a capital letter and end with a full stop. ↩

-

According to the OED (s.v. ‘Phrase, n.,’ 2024), a phrase is defined as anything larger than a word. However, this is clearly incorrect, as the clause (and simple sentence) ‘I dispute this definition.’ contains two one-word phrases, one of which consists of just a single letter. ↩

-

In Dutch: Algemene wet bestuursrecht. ↩

-

The current practice in the Netherlands is that changes of legislation are published in an official document that contains the change decided upon. Legislation consists of a new regulation and the set of changes made over the years. The whole set of these documents is the official source of a regulation. For practical purposes, after every change a new aggregated version of the regulation is published. The aggregated version of a regulation is what is used as a reference, although this is not the official source. ↩

-

Groups of people, or organizations like e.g. corporate bodies. ↩

-

FRBR mentions four categories: concepts, objects, events and places. ↩

-

If a source component does not have a ‘text fragment’, as is common for e.g. chapter (that are often just marked with numbers) or paragraphs (which often are even unnumbered), the text fragment slot remains empty, and only the information on source components is registered. This is necessary for keeping track of the document structure. ↩

-

In European regulations there can be a difference between the ‘date of entry into force’ (the date when the regulation becomes legally binding) and the ‘date from which provisions are to have effect’. The ‘date from which provisions are to have effect’ is the date when the regulation's rules or provisions start being applied in practice. It is used for allowing Member States time to implement new regulations. ↩

-

In European regulations there can be a difference between the ‘date of entry into force’ (the date when the regulation becomes legally binding) and the ‘date from which provisions are to have effect’. The ‘date from which provisions are to have effect’ is the date when the regulation's rules or provisions start being applied in practice. It is used for allowing Member States time to implement new regulations. ↩

-

However, one can choose to build and use any other interpretation scheme for interpreting of regulatory texts within the framework presented in this chapter. ↩